Preserving my latest for Next Avenue which, sadly, will not be around much longer thanks to federal funding cuts to PBS. I can only imagine the letters she’d be writing today.

After she died, I learned Gram had a flair for a strongly worded letter — and regrets I never knew

I spent the first eight years of my life in a blissful bubble with my grandmother Martha. She worked as a bank teller and was separated from, but still entangled with, my gregarious grandfather George, who would occasionally take us out for fancy dinners or whisk us away on a PSA jet to San Francisco to the horse races. He was the love of her life and the bane of her existence.

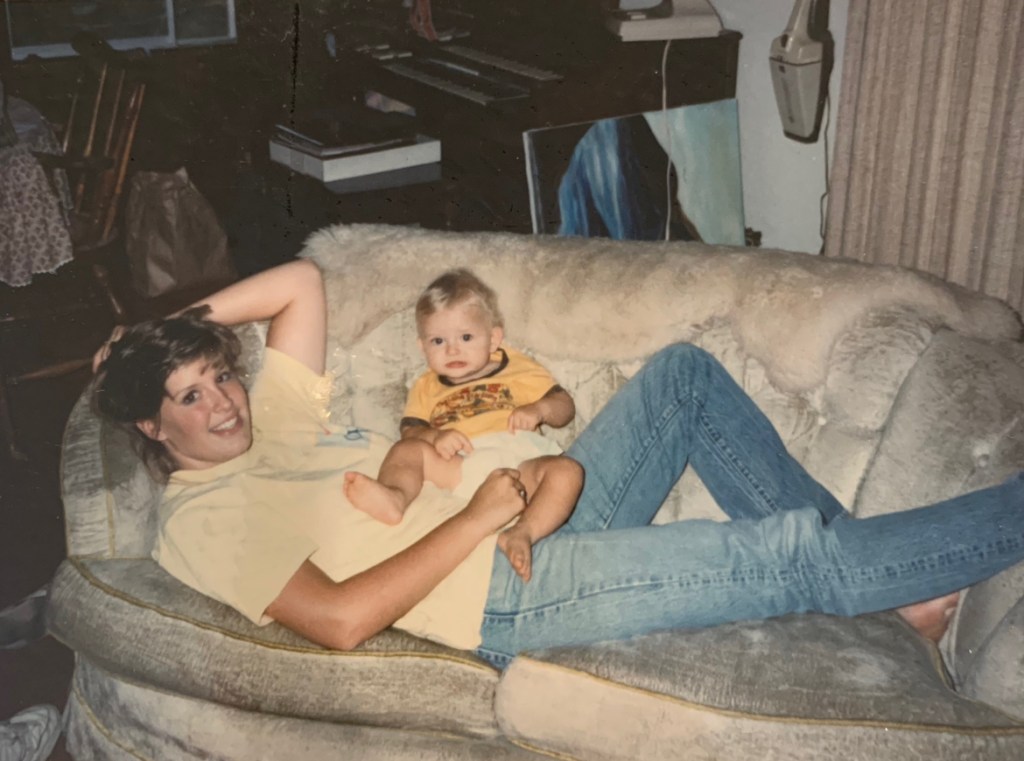

I came to be with Martha — I called her Gram — as a baby when it became clear that my mother was unable to care for me due to mental health issues. I lived with Gram in the historic Chase Knolls apartments, an idyllic, predominantly adults-only community in Sherman Oaks, California.

Born of a generation that kept secrets, she was strong and introverted.

We were extremely close and when I was a young adult, she was typically my first bright and early Saturday morning phone call when my friends were still sleeping. She was the greatest model of gratitude and positivity in my life. Born of a generation that kept secrets, she was strong and introverted. Her small circle of friends consisted mostly of three of her five sisters who lived nearby. Gram lived a quiet, humble life.

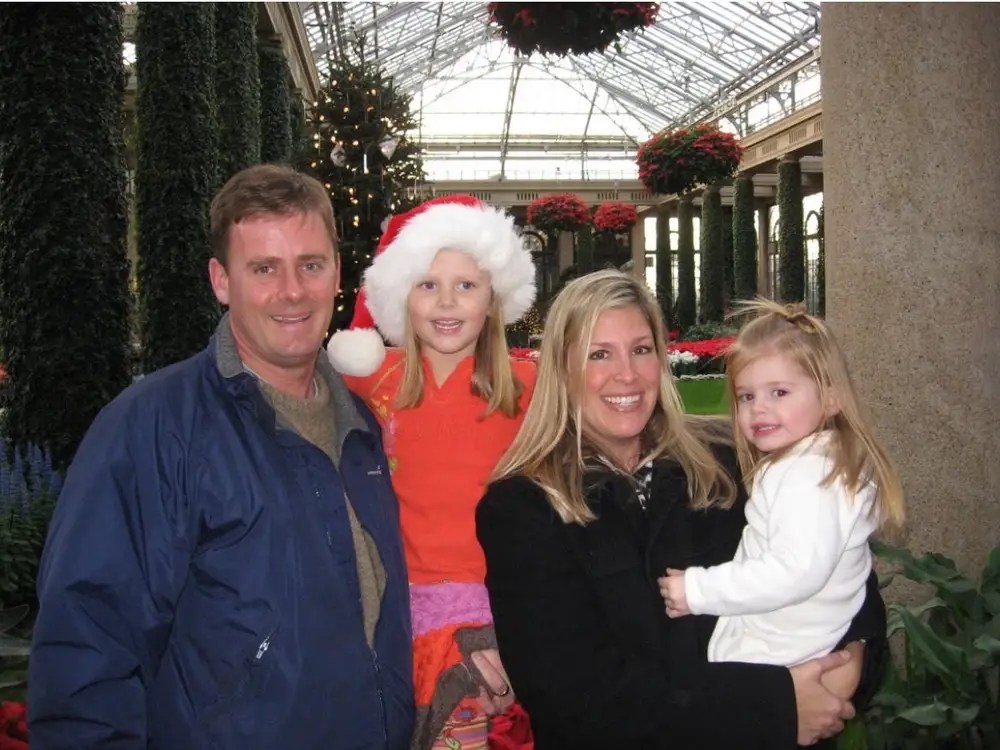

Easter was her favorite holiday and I have fond memories of the annual family reunion style picnics at a local park. By the time Easter 1996 rolled around, the annual picnic had long since evolved into gathering at my great-aunt’s home in Encino, California. I looked forward to it every year, knowing Gram would bring Armenian-style rice pilaf to go with the ham, tabouleh and asparagus.

That year, on our drive over to her sister’s, she complained about an ache in her right shoulder. I massaged it in the car and suggested she see a chiropractor.

I wouldn’t know that the breast cancer she’d had a partial mastectomy for a couple of years earlier had returned and metastasized into bone cancer until Mother’s Day weekend when I went to visit her and was shocked at her suddenly skeletal appearance. It was the final time we would spend together in the apartment where I’d grown up with her, and the only place that had ever felt like home.

We’d buried her mom, my sharp as a tack until the end great-grandmother, who passed peacefully after washing her face one evening in March. She was 96 and, according to Ancestry, a distant cousin of Abraham Lincoln.

Five months later, on August 13, 1996, Gram died and the one sure and constant thing in my life was gone. I was angry that no one told me she was sick. She likely didn’t want to worry me because I had my own problems. Knowing what I know now, maybe she thought she deserved it somehow.

The Contents of a Folder

After she died, I drove the 100 miles from my place in the San Bernardino, California mountains to the Valley to collect what I wanted to keep of her belongings. It was a blur and to this day I regret not taking her Nat King Cole and other record albums. Among the few things I had the wherewithal to keep was a large blue folder filled with smaller folders containing photos, newspaper clippings, letters (lots of letters) and loose notebook pages filled with the innermost thoughts of a tortured soul. It would be many years before I sat down and really sorted through it all.

Gram wrote eloquent, intelligently thought out letters tempered with an appropriate amount of outrage and snark to editors of newspapers, radio and news outlets.

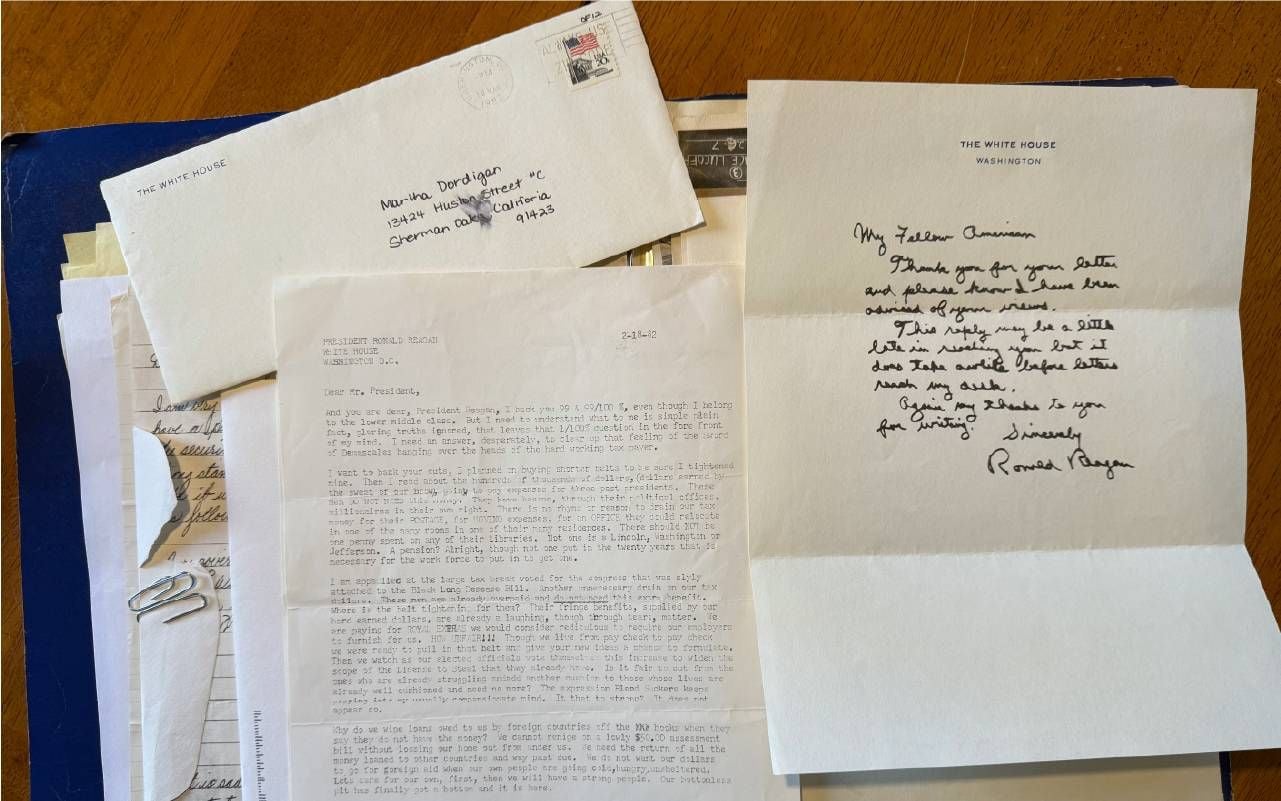

I learned she had a flair for the strongly worded letter. There are letters to Presidents Ronald Reagan and George H. W. Bush, expressing concern over everything from tax cuts to conflict in the Middle East. Gram wrote eloquent, intelligently thought out letters tempered with an appropriate amount of outrage and snark to editors of newspapers, radio and news outlets.

In a letter to President Ronald Reagan dated February 18, 1982 she writes, “I want to back your cuts, I planned on buying shorter belts to be sure I tightened mine.” She went on to share that she was “appalled at the large tax break voted for Congress that was slyly attached to the Black Lung Disease Bill.”

She encouraged the President to “crack down on the power people, not just the helpless.” She signed off, “I am sincerely dreaming of satin sheets but thankful for my cotton set, a 59-year-old eight-to-five brown bagger, who respects and am proud of our President. Female. Martha Dordigan.” She received a ‘handwritten’ thank you note — a “My Fellow American” stamp — on White House stationery the following month.

Not surprisingly, many of her concerns for our country are mirrored in today’s news. Her published letter to the editor of the Daily News in 1989 begins, “What has happened to the American way of life? When an elected official can call efforts to get rid of greedy, sleazy and power-hungry men “cannibalism,” we have sunk to a new low.”

While Gram was open minded, I learned she apparently had her limits. In an undated draft, typewritten in all-caps exasperation she writes, “Now I have heard everything! The American taxpayer is about to foot the bill for the study of lesbianism in seagulls, yes, I said seagulls! Does anyone really care!”

I read with great amusement a letter she wrote to Oprah Winfrey in 1988 singing the praises of her talk show, and offering thoughts on how to cut back on commercials to make it even better.

‘Poems/Homelies/Thoughts’

Tucked between clippings and letters to the powers that be is a folder that is labeled “Poems/Homelies/Thoughts.” Its contents stopped me in my tracks.

On a faded piece of notebook paper, in ink that has turned a brownish maroon, she wrote, “I was born February 2, 1923. It is claimed by some that if you concentrate hard enough and let your memory sink inward, you can remember being born. I cannot. I do not want to remember. All babies are cute, even the ugly ones, so I guess for a short time I was cute. Then my mother took me home and then I died.”

“I was born February 2, 1923. It is claimed by some that if you concentrate hard enough and let your memory sink inward, you can remember being born. I cannot. I do not want to remember.”

While there is no context around this, it’s written just above a poignant essay about my Uncle Gary. In May 1975, Gram’s only son, 32, was killed in a small plane crash, along with the wealthy real estate developer he was training, on Frasier Mountain in Southern California. It is written from the perspective of Gary’s car waiting for him to return to the Van Nuys airport. I published and titled it “Little Blue Maverick” in 2011 and continue to receive comments from people who knew him.

I never knew the excruciating regret she carried as I read, weeping, the water stained page — from her tears? — about how cold she was to Gary the last time she saw him one month earlier at our annual Easter picnic. Not yet legally divorced, he’d brought his new girlfriend and Gram didn’t approve.

In a subsequent entry referencing my mother: “God, can I thank you for leaving my girl with me? I do not deserve her either. My beautiful, sharp baby girl. She knew that I didn’t know how to give her the right answers. She knew even before she could talk. I still see her eyes, knowing I did not know.”

And yes, there is bittersweet irony in the way she was able to give me what she wasn’t able to give my mother.

Just below, on the same page she recounts, “something precious and delightful that Jennifer did when she was barely 4 years old.” We’d gone to dinner in Laguna with my grandfather the night before his horse was going to race at Hollywood Park. While we waited to be seated, I sidled up to an older boy in line, looked over my shoulder and out of the corner of my mouth said, “Irish Mafia runs in the 4th.”

Almost 30 years after her death, I still feel my grandmother’s presence — this blue folder, a portal into her mind. I have now read and reread its contents countless times in an effort to squeeze out any new detail. Had her life circumstances been different she might have been a journalist. Her writing has informed my own.

Her distinctive scrawl, the depth in which she expressed privately the things she didn’t say aloud, reveal so much about the woman I was closest to in this world and the cruel fact that I hadn’t really known her at all.

***

An additional word from Gram is a cautionary sentiment to never take whatever time we’re given here for granted.

“I have lived my life without adventure or real risk. What a shame, what a waste. I have not really lived.“

Thank you for reading,

xo Jen